Having finished Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’, I still find myself puzzled by exactly what the author was trying to achieve, and feel more then ever convinced that in the nineteenth century, authors often started writing a novel unsure what they were trying to accomplish, and often ended up with something else.

Having finished Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’, I still find myself puzzled by exactly what the author was trying to achieve, and feel more then ever convinced that in the nineteenth century, authors often started writing a novel unsure what they were trying to accomplish, and often ended up with something else.

Not as if I’m saying that in this century, authors always know what they intend to achieve when they start out, or that the work doesn’t change in emphasis, or even the importance of characters alter, as the story develops; but no modern author would get away with the ambiguity of theme and content which does seem to characterise so many Victorian classics in particular, and I find this fascinating.

I assume Hardly wished to depict two things; how a noble character could rise above adversity, and also, how leading a secluded life, one in fact, in ‘idyllic’ rural surroundings, might not preclude a man or woman from tragedy and intense passions.

He does this; but with uneven emphasis and success in depicting the said passions, and their changing nature, and with rather a lot of set comic pieces to offset the tragedy, which carry on too long, at least for modern taste.

The four main characters – Gabriel Oak, Bathsheba Everdene, Sergeant Frank Troy and Boldwood (I’m not sure his first name is ever given; anyway, I didn’t feel on first name terms with him) are involved in melodramatic relations which seem all the more striking for being set against a peaceful, traditional rural background some time between 1815 and 1875 (the date of the publication of the book).

It is an interesting read; as I have said, I like the character of the heroine, who dares to try to be a woman farmer in Victorian times. The weaknesses in her character that enable the story to take place are fully believable in a pretty and spirited young woman, and don’t detract from the heroine’s general appeal for the reader (or this one, anyway). The main one is her vanity, which is an aspect of her valuing too highly superficial attractions to the detriment of placing a true value on sterling qualities which may be hidden. Accordingly, her inability to see the worth of Gabriel Oak, and her corresponding inability to perceive the worthlessness of Troy as a potential husband to a hard working farmer, is well thought out.

Gabriel Oak is an admirable, if not especially interesting, character, and is well drawn, though I would have liked to know more of his fluctuating emotional states. Sergeant Frank Troy is an intriguing example of a superficially attractive and charming but unscrupulous and highly unreliable man, and Boldwood is an equally interesting example of a dangerously repressed and potentially violent and obsessive man. The minor characters are adequate for the roles they play, but rather in the nature of stereotypes.

The structure is also good. There are two climatic scenes in the novel. The first, which is very successful, comes about two thirds of the way through. Here, Bathsheba and Troy stand looking at the corpses of the girl he has seduced and deserted, Fanny Robbin, and her newborn baby.

This is tellingly depicted:

’He was gradually sinking forwards. The lines of his features softened and dismay modulated to illimitable sadness. He sank on his knees, with an indefinable union of remorse and reverence on his face, and bending over Fanny Robbin, gently kissed her.’

Bathsheba’s jealousy and anguish overcome her pride and pity for ‘your other victim’ and she hysterically demands that Troy kiss her too. Brutally, he refuses; ‘You are nothing to me – nothing.’

At this, Bathsheba rushes out of the house, and Troy soon goes himself. Their very short marriage (it lasts about three months) is at an end.

This scene is vividly portrayed and dramatically effective.

The second climatic scene , which in fact constitutes the chapter which decides the fate of the characters in the whole novel, is a good deal less satisfactory. It’s recounted in a flat, cursory way (rather like the writing I was doing this morning, sigh) and fails to bring a sense of dramatic satisfaction to the reader.

The obsessive and reclusive Boldwood has become fixated with the notion of marrying Bathsheba after she sent him a facetious valentine. Troy’s whirlwind courtship of her frustrated his previous plans to marry her, but after it is wrongly assumed that Troy has been drowned, Boldwood hopes that he might persuade Bathsheba to marry him when Troy can be presumed dead after seven years.

Over a year passes. Oak is now working for Boldwood as well as Bathsheba, and shows no jealousy of his employer when he finds out that he plans to marry her. This seems to demonstrate remarkable self-restraint. Oak is depicted as fairly devout, and one assumes his praying helps him to overcome feelings of resentment and envy of Boldwood. He accepts, it seems, that having lost his former social status, he no longer is in a position to pay court to her, and whether he regrets the unimaginative and unromantic way in which he originally paid suit to her in the comic scene of his proposal, is not revealed.

The uneven access the narrator has to Oak’s various moods and attitudes towards the other characters in the book is one of the main weaknesses in the story. We are told in some detail how Oak is able to accept his loss of his status with stoicism, but not how he is able to bring himself to accept that Boldwood ‘deserves’ Bathsheba. I assume the first is meant to be a pointer to the second. Also, he approves of Boldwood as a suitor for her, while he does not approve of Troy, whom he rightly considers to be immoral and unreliable. He does not, however, seem to notice that Boldwood is potentially dangerously obsessive.

The mirthless Boldwood holds a Christmas party. Despite the ample food, music, and roaring fires, nobody enjoys it. Things are made worse by the fact that Troy has been seen in the area, and Bathsheba doesn’t know it. Bathsheba is hectored by Boldwood into agreeing to marry him in nearly six years’ time, on the grounds that in sending him that Valentine in the wrong spirit, she has inflicted misery on him.

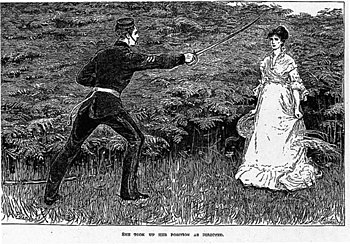

The unlucky girl is in the hall when it finally dawns on Boldwood that his guests look at him oddly. As he demands the reason, Troy arrives. He has been living an itinerant life since he left her, and is fed up with it. He orders her to come home with him.

Seemingly horrified (we never are told just what her feelings are at this point) Bathsheba shrinks away:

‘The scream had been heard a few seconds when it was followed by a sudden deafening report that rang through the room and stupefied them all. When B had cried out in her husband’s grasp, Boldwood’s face of ghastly despair had changed. The veins had swollen and a frenzied look had gleamed in his eye.’

Troy ‘Uttered a long and guttural sigh; there was a contraction, an extension, his muscles relaxed, and he was still’.

The very brevity of this depiction in the second sentence has a good deal of skill, but it cannot make up for the moment of high drama being recounted largely in the passive and in the perfect tense (to be pedantic). This has a distancing effect and much of the drama is dispersed. It would have been a good way for a novelist to recount something really distressing, as the sudden death of the unpleasant Troy is not, but leaves the reader unsatisfied in this, the climatic scene of the whole novel.

The very brevity of this depiction in the second sentence has a good deal of skill, but it cannot make up for the moment of high drama being recounted largely in the passive and in the perfect tense (to be pedantic). This has a distancing effect and much of the drama is dispersed. It would have been a good way for a novelist to recount something really distressing, as the sudden death of the unpleasant Troy is not, but leaves the reader unsatisfied in this, the climatic scene of the whole novel.

After this, the novel does rather peter out. Bodlwood is discovered to be mad, and the death penalty in his case is commuted. Troy’s widow and Gabriel Oak’s wedding seems inevitable, and the delays before it happens, with Oak threatening to leave the country (presumably in order to escape his seemingly hopeless passion for Bathsheba) did not make it seem any less likely to me.

I liked the fact that in putting up a memorial for her errant husband, Bathsheba demonstrates that she has acquired the very quality she has admired in Oak before, a stoic ability to endure life’s injustices without engaging in self pity or low minded acts of retaliation to those who have frustrated our personal desires. She buries him with Fanny Robbin, and the tombstone he erected for her commemorates them both. Bathsheba was earlier the one who replanted the flowers on Fanny’s grave, when a downpour had washed away Troy’s handiwork. She has matured and grown in emotional stature to become the worthy mate for Gabriel Oak that she was not before.

I just hope that Bathsheba finds him physically attractive; that she obviously did not at the beginning, is shown by how she does not even acknowledge him when he gives her money to pay at the toll gate where he first sees her. However, he is described as ‘a fine young man’ and we gather he is well made enough, so I assume that though the Victorian author could not make any direct statements about such a matter, that he has come to appeal to her physically too.

I saw various resemblances to George Elliot’s ‘Adam Bede’ in some of the themes in this novel, including that of a seduced and pregnant unmarried girl, a young woman mistakenly choosing a dashing and unreliable admirer rather than the steady and less glamorous one, the stoic, hard working and devout hero, the depiction of ‘traditional’ rural life and traditions, and the contrast between the ‘peaceful’ countryside surroundings and the strong passions of the main characters.

Would I recommend it? Yes, as I say, it’s an interesting read, and I found the plot far more believable than, say, ‘Tess of d’Ubervilles’ or ‘Judge the Obscure’. Still, the somewhat sketchy depiction of Troy, who is after all, a character central to the novel, and the equally threadbare depiction of Bathsheba’s growing passion for him and her quick disillusionment with him (she says ‘I may die soon’ implying a general weariness with life only weeks after she marries him) make for weaknesses in the development of the plot (even the wedding takes place ‘offstage’ in ‘Casterbridge’(Oxford?) .

There are circumstances where a writer leaving a character’s mental life unknowable to the reader, or perhaps only partly known, can make him or her all the more intriguing to the reader, but I didn’t find this to be so with Troy, for the simple reason that Hardy devotes a whole chapter to revealing Troy to the reader through ‘tell not show.’

Next Week: Beginning on my re-read of Anne Bronte’s ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’.

5 Responses

Interesting analysis, Lucinda. I have to admit that I haven’t read FFTMC, though I’ve a soft spot for Hardy – ‘The Mayor of Casterbridge’ is my favourite. Another one to add to my ‘to-read’ list…

Thank you, Mari. You’re one up on me with ‘The Mayor of Casterbridge’. I’m starting on re-reading Anne Bronte’s ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ and I remember I really enjoyed its gothic theme. I hope you may add that to this considerable reading list of yours, which must be a long and winding scroll indeed,a bit like those ones wizards or courtiers were always depicted as consulting in comic books..

You’re not wrong, Lucinda! 🙂

I’ve haven’t had the chance of reading this yet, I’ve only seen the movie. I’m not sure how exact it is, but I’m guessing the book explains a lot more. The relationships between them all didn’t come across very well to me in the movie, it was a big mess that didn’t make much sense

Thanks for commenting, BB. Ah, I was wondering what the film was like. I think it would have to be very clearly presented to make the motivations clear. It’s weird, Hardy had some good ideas in this,particularly for characters, and he didn’t seem to me to make the most of it.

I’m going to re-read Anne Bronte’s ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ next. I’d be interested to know what you think of that; I think she’s sadly underestimated, particularly compared to Emily Bronte.