Those ‘How To’ books on writing seem generally to lay less emphasis on endings than on beginnings; of their advice about endings, I can only remember that they said that you should resolve the conflict that drives the plot and leave the reader feeling satisfied. James N Frey in ‘How to Write a Damn Good Novel’ says that you ‘must have the good climax and resolution to the story that you hinted you would deliver earlier’. That about sums it up; James N Frey’s brilliant at that.

While by definition you won’t lose the reader of that particular book by having an unsatisfactory ending, you may well for future books; he also warns against ‘playing tricks with the reader’; I haven’t come across such an ending in ages, but I suppose they would be of the ‘and it was all a dream’ variety.

He points out that playing ‘clever tricks’ on a reader will only annoy the reader, and it’s true. A few years ago, I read a really infuriating story that kept giving false dramatic resolutions which were then explained away as fantasies in the protagonist’s mind; after about two of these I threw the book in the charity shop box, and it was only innate meanness that prevented me from hurling it into the recycling. As I’m so stupidly stubborn it usually takes a lot to make me leave a book unfinished, I see what he means about avoiding at all costs that trick ending; the reader won’t appreciate your cleverness; the reader will feel cheated.

There’s also a problem, of course, with books that only form part of a series; the reader always feels slightly cheated here, too, in that the resolution of the main conflict hasn’t happened – yet again; although the author will have explained that this is in fact a series, this still remains true; and the longer the series continues, it seems to me, the greater this sense of frustration becomes. Minor conflicts driving the plot are variously resolved, but that final resolution is kept on hold; that tantalizing of the reader requires a lot of skill, like a coquette of olden times keeping an admirer on a string for months or years…

Then, there’s the whole question of the nature of that satisfactory resolution; it’s here that we see how much the imaginative world we create is just that – artificially constructed. After all, in real life, there are rarely satisfactory conclusions of any sort; evil doers go to their graves unpunished, at least as far as this world is concerned (the case of the infamous Jimmy Saville in he UK is a recent example); unselfish people go unrecognized; people who share true love are separated; and as often as not, wildly dramatic situations sometimes just fizzle out and defuse over time.

However much we may be prepared to accept that this is so of real life (and a lot of people aren’t) we don’t want to come across it too much in stories. We want a clear and satisfactory resolution of some sort and we don’t want our sense of justice to be too outraged; to deliver this resolution may be quite a complex matter, as these days we don’t quite believe in the same divisions between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ characters that seemed so clear to earlier writers (as always, Shakespeare is an exception).

Generally, though, the modern reader still doesn’t want evil doers to get off scot-free, or heroics to go totally unrecognized, or for virtue to have no sort of reward at all (even if it’s only hinted that this reward will come in the next world). There are, of course, huge differences between comedy and tragedy regarding the outcome of stories, and tragic outcomes unfortunately often come across as a lot more realistic in tone than the happy endings, which so often seem rather contrived.

Thinking back on various classic novels that I’ve read or re-read or partially revisited over the last few years, it occurs to me that in fact a number of these don’t have endings which are generally regarded as satisfactory. This is interesting; they have their supporters; but the resolution to the basic moral conflict in some of these stories is sketchy, and in other’s it is arguable that the author has made one of those seven deadly mistakes about which James N Frey warns and ‘not followed through’, either through softening towards the character who has served the part of the villain of the piece, or possibly through a misguided wish to introduce an element of realism in a story not strictly speaking realistic.

I’ve said too often to need to need to repeat what I think of the unjustly good fate meted out by Elizabeth Gaskell to the unscrupulous opportunist Charley Kinraid in ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’, and I’ll go on to ‘Vanity Fair’ and ‘Wuthering Heights’).

For instance, the fate of Becky Sharp in ‘Vantiy Fair’ is wholly unsatisfactory; whatever moral Thackeray wished to point in making her thrive, while most of her victims come to fairly dismal ends, one leaves the story with a sense of jaded weariness, or anyway, I did. This all seems to be in line with the strange combination of sentimentality and cynicism which characterize Thackeray’s writing, and make his general depiction of characters and the relations between them unsatisfactory, too; his good characters are for the most part lacking in any capacity to learn, it seems, from unpleasant experiences or to discriminate between admirable and contemptible love objects, while his ‘bad’ characters almost invariably remain just that – mean and exploitative; the result is that his world is oddly static, his ‘vanity fair’ and his characters very much the theatre and puppets which he dubs it in the last sentence of the book.

A great many people admire Becky Sharp as some sort of feminist heroine – and while I see her as admirably independent and endowed with a justifiable contempt for the absurd injustices of the world in which she lives, I personally find her repellent, treacherous and incapable of love or loyalty as she is. We leave her living a life of smug respectability on the money she has stolen from her last victim Joseph Sedley, the one who would have been her first, had it not been for the interference of George Osbourn.

Amelia having been brutally disillusioned about her former idol Osbourn, and having found a safe haven in the arms of the Dobbin, surely one of the most boring male leads ever in literature (I can’t call him a hero as this book is sub-titled ‘a novel without a hero’) all supposedly ends happily (it is only to be hoped that she doesn’t find him as physically unappealing as one might expect from her indifference to him for the previous 550 pages). After the drama in much of the previous story, I found it an anti climax.

If Becky’s fate is meant to demonstrate that ‘the wicked thrive in this vale of tears’ then this is hardly reflected in the fate of a lot of other less than admirable characters, many of them quite astute citizens of vanity fair themselves, who come to dismal ends. The old lecher Sir Pitt Crawley is reduced to idiocy and tormented by callous nurses after a stroke, his sister the pseudo revolutionary Miss Crawley is only saved from pathetic loneliness in her last months by the kindness of her niece by marriage Jane, while the wretched older Sedleys eke out an existence of penury and misery. Becky’s estranged husband Rawdon  Crawley, a professinal gambler and rascal himself, humiliated by Becky’s betrayal, succumbs to yellow fever in a tropical island, while after his son’s death at Waterloo, the older Osborn leads a life of joyless bitterness.

Crawley, a professinal gambler and rascal himself, humiliated by Becky’s betrayal, succumbs to yellow fever in a tropical island, while after his son’s death at Waterloo, the older Osborn leads a life of joyless bitterness.

Perhaps Thackeray was advocating the necessity of religion to add meaning to wordly sufferings, but it has been pointed out before that all of his characters – even Becky – do in fact, profess religion.

I felt the same way about ‘Wuthering Heights’; the ending doesn’t leave the reader with a sense of satisfaction. Whatever one may think about this book, it can’t possibly be said to lack excitement, drama or larger than life characters. But again, I found the conclusion to the conflict and moral issues raised lacking in any satisfactory sense of resolution. While the conflict between the inhabitants of Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange finds a happy resolution in the love between the Hindley’s son Hareton (raised and even regarded with affection by Heathcliff, and so in many ways, his son too) and the younger Cathy, the issue of Heathcliff’s malevolence and wrong doing is never properly addressed.

In fact, he goes to his grave unrepentant, even fully convinced of being in the right and insisting that he has done no injustice. The slight mellowing he shows at the end towards Hareton and Cathy’s love is based on increasing indifference to this world rather than any advance in spiritual understanding, and his obsession with the older Cathy remains relentless to the point of actually causing his death. If this rather empty conclusion is in fact the moral of the story, then it seems a very shallow one for so clearly spiritual a writer as Emily Bronte.

While the twisted old Joseph may ‘look about to cut a caper’ when he gloats that the evil doer ‘grinning at death’ means that ‘the devil has made away with his soul’ I think my own reaction of dismay at the bleakness of it all is fairly typical of readers.

While Heathcliff’s lack of insight may be realistic, the circumstances of his death aren’t; one gathers from the time frame that he, a healthy man in early middle age, has died after starving himself for less than a week. As we may assume he hasn’t been depriving himself of water, it wouldn’t be possible for him to die from of starvation so quickly, though he might well be in a state of collapse. Heathcliff’s body is found staring out of an open window, and it seems fair enough to assume that a supernatural element has played its part in his end.

It is dismal that Heathcliff is unable ever to appreciate the extent of his wrongdoing, or to wish to make amends– and his indifference to Nelly’s unimaginative but courageous warnings about the spiritual consequences of the hate filled life he has led, and the misery he has caused, is taken by some readers – I think entirely mistakenly – as evidence that the author shared his conviction about this. I gather from various poems of Emily Bronte that she was fascinated by the spiritual fate of he unrepentant, Byronic sinner, and one may conclude that Heathcliff was her literary experiment in this direction.

Interestingly, the last, evocative sentence of the book – Lockwood’s reflections on ‘the quiet earth’ as he stands at dusk by the graves in the churchyard on the moor, surrounded by ‘harebells’ and fluttering moths, is certainly inspired; but while it distances the reader to some extent from the excesses and malignant passion that has come before, it can’t really make up for the lack of a satisfying conclusion.

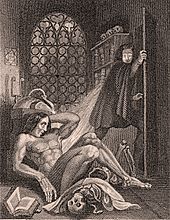

By contrast, ‘Frankenstein’ does give a resounding conclusion to the tormented monster’s obsessive hunting down of his contemptuous creator. When ‘the creature’ realizes that he loved the now dead Frankenstein as much as he hated him, and mourns over his body, the text becomes purely tragic, for all it’s theatrical nature; –

‘ “Wretch!” I said. “It is well that you come here to whine over the desolation that you have made…Hypocritical fiend! If he whom you mourn still lived, still he would be the object, again would he become the prey, of your accursed vengeance.”…

‘”Oh, it is not thus – not thus!” interrupted the being. “…No guilt, no malignity, no misery, can be found comparable to mine. ..I have devoted my creator, the select specimen of all that is worthy of love and admiration among men, to misery…I shall die…”’

Melodramatic as this exchange between the Captain and the monster over Frankentstein’s murdered corpse may seem when the words are read cold, without the build up of all the tension and horror that has come before, they are fitting reflections for a being who has gone in for the excesses that he has. For me at least, it is only something on the same lines spoken by Heathcliff that could have made me feel compassion, rather than the pitying disgust that I do, for the character.

(By the way, for those who wish to read the ‘Frankenstein’ original, it’s free today on amazon

With our modern complex notions of the combination of good and bad in all characters, real and imaginary, and our lack of a naïve polarisation between good and evil, writing endings both fitting and satisfactory for wildly erring – gothic or penny dreadful inspired characters is a challenge. I for one find a satisfaction and tragic grandeur in the ending of ‘Frankenstein’ which is lacking in other depictions of the final consequences of devoting a life to evil doing, whether it takes place within the confines of polite society – ‘Vanity Fair’ or is expressed through unrestrained brutalities in isolated moorland as in ‘Wuthring Heights’.

I remember laughing at the absurd moral guidelines that were laid down for short stories by a best-selling woman’s magazine some years back : – ‘adulterers and wrongdoers must be seen to meet fitting retribution’ but there is an element of truth in such guileless strictures nevertheless; for a satisfactory ending, brutal villains and heartless schemers should probably not be left finally gloating over their career of destruction with calm satisfaction and equanimity. They may very well go largely unrepentant to their graves, but they should at least not go, like Heathcliff, in a state of bliss.

Many readers may strongly disagree with my take on this, and I’d be fascinated to hear any thoughts on the matter.

4 Responses

One of the endings that made the most impact on me was Paul Gallico’s Poseidon Adventure. Where the film celebrates the vision and drive of Reverend Scott, the book ends by giving him a final kick in the teeth, leaving the reader feeling somewhat cheated. While I can appreciate the motivation for this ending, I cannot forgive it.

Another is Hannibal, the sequel to Silence of the Lambs. The film mangles the ending and gives Clarice a more classical victory, but the book’s ending gives her a different kind of victory that, initially, is a shock to the reader. The first time I read it, I threw the book away in fury, and it took several days of thinking about it to understand the genius of it. With either version, Hannibal Lecter himself is monstrous, heroic and victorious, a rogue at once charming and terrifying.

Ironically, with my own writing, I am quite determined to find an ending that feels right. With Suzie and the Monsters, for example, I wanted to give Suzie a grand climactic victory, but realised eventually that the ending needed to be bitterly unclimactic – that the reader could not be allowed to share in some illusion of victory. Contrast this with Liam Neeson’s Taken, which is relentlessly upbeat despite the horrifying subject matter.

Your comment about the charity shop makes me smile. Books that I have particularly hated will go in the bin rather than the charity shop…

Series are tricky and unfortunately have conflicting demands. From the reader/viewer perspective, the stories should wrap as neatly as possible. For example, Buffy the Vampire Slayer was written very satisfyingly, with each season’s climax finishing the thread that had run through that season. Contrast that with Smallville, where the season finale was inevitably a cliffhanger that meant you had to wait impatiently for the next season to start for the story to resolve – which is great from the network’s perspective because it keeps attention and interest high for the next series, but it’s deeply frustrating for the viewers. It’s especially annoying if access to the series is difficult. The number of cliffhangers I’ve seen over the years where I have no idea what happened next is depressing.

That’s very insightful, Frank; I didn’t experience any sense of let down with the ending of ‘Suzie and the Monsters’ as a matter of fact, the people who did the most monsterous things, the people traffickers, having been defeated. I know just what you mean about series where you never see the conclusion.

Interesting post, Lucinda. One thing that I’ve always admired about Wuthering Heights it the sense of delicate resolution and synthesis that comes at the very end, when all the main protagonists are buried close together in a symbolic representation of the harmony that eluded them in life. The main body of the book is stormy indeed; the end is akin to the calm that follows the storm.

It’s true that real-life situations as often as not just fizzle out, rather than come to any kind of satisfactory conclusion. Many real-life stories fail to point to any particular moral, and don’t really have much of an ethical core. I admire writers who are willing to allow some of that essential realism to creep into their writing. And yet … we do crave resolution, don’t we? Perhaps we look for satisfactory endings in fiction precisely because they’re rather rare in reality? I’m undecided about this.

I suppose in the case of series it depends on how it’s done, I think. I’m quite partial to Patricia Cornwell’s Scarpetta novels. Although there are ongoing elements, in terms of the development of the main character, each book is nevertheless a complete story-in-itself; you don’t have to read them in any particular order, and you don’t have to have read others for one to make sense.

Very subtle, as ever, Mari, That ‘Scarpetta’ series you mention sounds like an excellent example of how not to frustrate the reader of a series. There certainly seems to be an appeal to resolution in fiction precisely because we just don’t get it as often as not in real life. I think James N Frey’s advice about how a writer must always deliver what appears to be promised in the premise, and in the main body of a novel is relevant here. If there is a certain ambiguity in tone from the beginning, then an ambiguous ending is fine.

Re: ‘Wuthering Heights’ I think if Heathcliff had repented, I would have enjoyed the harmonious end as much as you were able to. As I’m sure I’ve droned on about before, one of the problems that Emily Bronte didn’t foresee in giving such an ambiguous ending to her story is that so many readers misinterpret the work as a love story, actually seeing Heathcliff as a hero – but stories are always open to misinterpretation. Samuel Richardson actually wrote introductions telling people how they must read his works, but of course, they were largely ignored (WINKS).