Recently, I’ve been reading another classic I have been intending to get down to for years; Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’

Recently, I’ve been reading another classic I have been intending to get down to for years; Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’

To be unsparingly honest, I don’t know what I think of it; my feelings are mixed. I fid the style convoluted, but some of the descriptions are highly evocative, the characters are individual, and it’s a generally interesting theme – that of a young woman who wants to be an independent farmer at some point in that most patriarchal of environments, a time in the earlier part of the nineteenth century England (the precise date is never given, but it was published in 1875, and the writer refers the events as taking place in a former time period, perhaps some decades).

I assume it is post the time of the massive enclosures of the common land and the unrest caused by those, but even this isn’t clear, though they are never mentioned. The image is of an essentially unchanging, insular community, and the title, I assume (again, I haven’t read any of the literary criticism) is meant to be ironical in that intense passions and violent deeds, seductions and betrayals form a large part of the story (I duly note that it is a quote from ‘Elegy in a Country Churchyard’; I remember ‘doing’ that at seventeen in English Literature; I thought the first four verses inspired; the rest dull).

In fact, the passions and betrayals – with the exception of the unlucky seduced maidservant, Fanny Robbin – are largely confined to the four main characters, three men and a woman, who are not really typical of the rest of the community, being set above them either by natural talents (Gabriel Oak, who anyway comes from another village) and the oddly named Bathsheba Everdene, or social position ‘Farmer’ Boldwood, or both – Sergeant Frank Troy.

The rest of the cast are, it is true, motivated by the normal human passions, and fairly unheroic in general, although not invariably mean spirited. I vaguely remember hearing that Hardy was a great exponent of the simple virtues of country life (he must have found a willing acolyte in the later Charles Garvice, who thought it was a cure for wild young men, rather like a stint in the army).

Life for the people in this rural community in ‘Wessex’ is generally depicted as reasonably pleasant, if labour is hard, and the discomforts of life in a cramped, damp cottage without proper sanitation receive no notice (Gabriel Oak is presumably able to rise above such inconveniences as having no proper lavatory; after all, he is able to surmount most things, including losing his beloved to a man who doesn’t value her, and his fall from his former status as a farmer; Stoicism is his second name, and Steadiness his third).

In some ways, I preferred the extreme picture painted by Zola in his depiction of rural life around the same period in central France, ‘The Earth’.

There, passions run riot; greed is the order of he day, and the pastor has been driven out because the godless peasants refuse to pay their tithes. Lust, cruelty and incest are part of everyday life, and I have to say that in an extreme way it rang true for me of country life in highly isolated areas in England as recently as the late twentieth century. It made me laugh, as it reminded me of a certain area in North Devonshire in which I spent some years during my childhood, where the vicar had indeed been driven out by the locals (I played a prank in naming a particular village in the title of a book in the library in my own novel, ‘That Scoundrel Émile Dubois).

This, however, is meandering from the point; Zola made a thing of writing contentious novels that attacked religion and treasured illusions generally, and exploding the traditional French admiration of the stolid, worthy peasant, ‘Jacques Bonhomme’ was just a part of it. Hardy was fired by no such motives; it seems to me, by contrast, he wished in part to portray the delights of farming life in an age when it was under threat from growing industrialisation.

Bathsheba, then, is an unusual heroine by Victorian standards; she is an independent heroine who wants to make her own way in life. When her uncle takes the unprecedented step of bequeathing his farm to her, she runs the farm by herself. She does, through inexperience, run into some difficulties, but she is helped by the devoted Gabriel Oak, who in the former village where they both lived, before he lost his flock and his independence, was her rejected suitor.

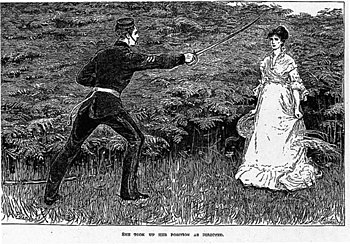

Trouble arrives the shape of the dashing, handsome, philandering and unreliable Sergeant Troy, who courts Bathsheba with displays of sword play and gallantry. Bathsheba is soon hopelessly infatuated with him, and ready to jeopardise her future independence to make him hers (marriage in early nineteenth century England deprived a woman of all legal rights and all her properly became her husband’s on marriage).

The author remarks: ‘When a strong woman recklessly throws away her strength, she is worse than a weak woman who has never had any strength to throw away’.

I can’t take exception to that; it’s still horribly true today; it is an unusual woman, who, once she succumbs to romantic attachment to a man, can see him or her circumstances objectively at all, this inevitably being bound up by the notions of romantic love and emotional dependency which woman are encouraged to cultivate.

There is more excuse for Bathsheba for adopting this course than many a woman in our own age. As a woman living in a small rural community in an age of unquestioned notions of female virtue and before effective birth control, she cannot indulge her passion for Troy outside marriage. In that case, when due disillusionment came, she could suggest a parting of the ways. Instead, she marries him.

I haven’t finished the book, but I can see that Sergeant Troy is destined to come to a bad end; he proves himself a ne’er do well, and refuses to take the sensible counsel of Gabriel Oak and so risks the harvest while engaging in a drinking spree with the labourers at the Harvest Festival.

We have seen nothing of Bathsheba and Tory’s married life, but we gather from her hint to Gabriel Oak at this time, ‘I may soon die’ that she is already, a few weeks after the ceremony, very unhappy and sees that she has made a fatal error.

A few weeks later, the run away servant maid Fanny Robbin turns up again, and dies in childbirth in a local warehouse. The reader, unlike the heroine, knows that Troy is her seducer, and that he would have married her except that she went to the wrong church, after which he left in a rage.

Troy is a strange character. Seemingly happy to forget Fanny Robbin before (one assumes he didn’t know that she was pregnant, as the dates would make it very early for him to do so at that time of their proposed wedding) , he undergoes a violent reaction of grief and remorse.

When by a series of unfortunate co-incidences, the poor girl’s body is taken to Bathsheba and Troy’s farmhouse, the superficial Troy furiously rejects the woman he has married in favour of his dead former love.

Reverentially kissing the dead girl’s face, he exclaims: ‘That woman is more to me, dead as she is, than you were, or are, or can ever be…You are nothing to me.”

He then spends all his (really, Bathsheba’s) money on a headstone for Fanny Robbin and leaves the area. Circumstances combine to give the impression that he has been drowned, and he stays away for many months. Meanwhile, the strangely obsessive Farmer Boldwood has resumed the persistent courtship of Bathsheba that Troy’s advent interrupted, and the faithful and steady Gabriel Oak continues to be just that, now employed as bailiff by both the traumatised Bathsheba and Boldwood.

This former dramatic scene, though extremely well depicted in Hardy’s usual melodramatic style, is unfortunately detracted from by the fact that we haven’t seen enough of Troy’s impulsive and superficial nature, or his quick boredom with life as a farmer and Bathsheba’s husband, to make it fully convincing. True, we have seen him desert Fanny Robbin after she failed to turn up at the ceremony, and we have seen him neglect the harvest, but the progress of the theme is too abrupt. More hints of the diverse and finally incompatible natures of the fickle Troy and the intense and loyal Bathsheba are needed to make it as dramatically effective as it could be.

Hardy is a great one for telling not showing. and he does this with a whole chapter devoted to Troy’s character, where we are told just what he is. This was probably in line with Victorian taste, but is considered inadequate in our own age, where readers want Troy to show them what he is.

Well, that’s my opinion of this climatic scene; what the general one is, I don’t know, because I’ve been lazy and left the literary criticism unread

(I haven’t even seen the recent film).

As I say, I have only read three quarters of the novel. In part it seems to be covering a theme to be found in various novels of both the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries (and also the twenty-first) that of an attractive young woman who has tow admirers, one of whom is steady and lacking in obvious charm, the other of whom is flashily charming, but unreliable.

Examples of this I’ve read include George Elliot’s ‘Adam Bede’ and of course (sorry everyone, for mentioning it again) Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’.

Hardy’s novel is complicated; of course, by the presence of a third admirer, and this is an original stroke. He is neither flashily attractive, nor steady but lacking in dash. Boldwood is handsome, but withdrawn; intense, but repressed. He is obviously a walking time bomb.

Next post; Some More Meandering Meditations on Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’.